Discover the latest exhibitions, programs, and special events at the AGA! Explore a dynamic array of artistic experiences that highlight diverse perspectives, renowned collections, and contemporary Canadian art. From thought-provoking art exhibitions and immersive installations to engaging workshops, tours, date nights and family-friendly activities, there's something for everyone.

Stay updated on seasonal highlights, artist talks, live performances, and exclusive members-only events. There's so much to see and do at the AGA whether you're a long-time art enthusiast or a first-time visitor, so if you're in downtown Edmonton, check out what’s on at the AGA and plan your visit today!

Exhibitions

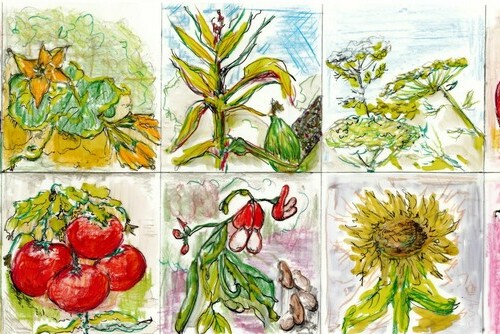

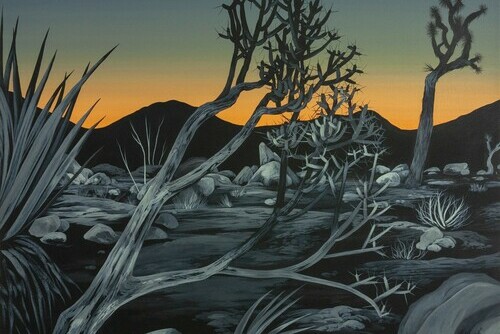

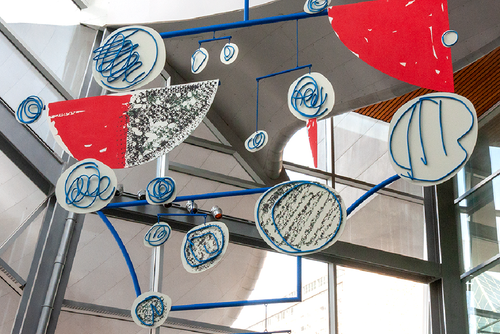

Current Exhibitions

Explore our latest exhibitions, where every visit offers a new opportunity to connect with captivating works and uncover fresh insights.

Past Exhibitions

Did you miss an exhibition or want to look back on a favourite? Find all exhibitions since 2010.