When planning what was meant to be a community tour of the AGA’s current exhibition Nests for the End of the World, I intended to draw on the exhibition’s curatorial statement and the artwork itself to remind us of what is now felt acutely: we are living in tumultuous and terrifying times.

These tumults and terrors register on political, environmental and personal levels, aggregating in many of us as uncertainty, hopelessness and depression. This exhibition, then, has asked artists to “offer responses to or coping mechanisms for [the] overwhelming circumstances” that face us, to offer in combination “hope and optimism [alongside] irony and humour.”

I had planned to lead the group on a literary tour of the exhibition, drawing connections between the artwork and the literary and critical texts that Glass Bookshop—the independent bookstore I co-manage alongside Matthew Stepanic—donated to the exhibition to help us all think through the art as well as the moments of political and environment crises we find ourselves in. I wanted to frame the tour around the work of Ann Cvetkovich in Depression: A Public Feeling, who reminds us that “discussions of political depression emerge from the necessity of finding ways to survive disappointment and to remind ourselves of the persistence of radical visions and ways of living.”1 More than ever, these frank discussions about the ways in which the conditions of the world—ongoing settler colonialism, the legacy of transatlantic slavery, the climate crisis, and now a widespread global pandemic—weigh on us (and on some of us more than others) remains a way to see us through to the other side, toward a livable future.

Leading a reader through an exhibition they aren’t physically experiencing and describing art they aren’t seeing and engaging with for themselves requires more description and space than what is available here, and so, instead, I’ll offer entry points to the conversations Cvetkovich might be gesturing toward, in hopes that you can take them with you as you view the artwork yourself, as many of the pieces are available to view via the AGA’s blog in the On The Spot! series.

I had planned to begin at Bruno Canadien and Niki Little’s Gifted, which sees pieces of ribbon in all colours suspended from the lit ceiling in a star shape, with projections of beadwork and a bundle of plants on two opposite walls. The artist’s statement foregrounds the essential practices of relation and exchange that not only form this work but are also central to Indigenous life; practices which, as the artists say, are “so fundamentally different and vital to colonial spaces.” With this piece, Canadien and Little call on an audience to foreground the “profound connections … and gestures of mutual understanding that give … the energy to keep going.” This piece evokes the work of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass and Billy-Ray Belcourt’s NDN Coping Mechanisms.

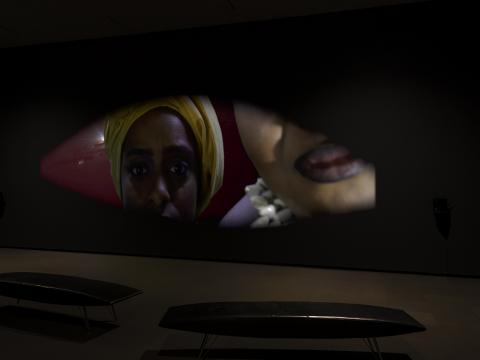

Camille Turner’s film Awakening takes up the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade and sees two African Diasporic travellers aboard a space ship encounter Gloria Smith, a Black woman from present-day Canada who hopes to travel back in time to stop transatlantic slavery from ever occurring. The two women reckon with the inescapability of time and the ways in which they are wrapped up in it; they recognize that, if successful, Gloria’s plan will save millions from “upheaval, trauma, enslavement and death,” but will also render them and their lives impossible, as underpinned as their existence is by transatlantic slavery. They are living “in the wake,” which Christina Sharpe articulates in its many possibilities in her book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being: “In the wake, the past that is not past reappears, always, to rupture the present.”2 In the wake of transatlantic slavery, in the wake of the ship of history and their spaceship now, history reverberates. And, as Saidiya Hartman writes in Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, “The past depends less on ‘what happened then’ than on the desires and discontents of the present. … When is it clear that the old life is over, a new one has begun and there is no looking back? From the holding cell was it possible to see beyond the end of the world and to imagine living and breathing again?”3 Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, Hartman’s Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route, and Kathryn Yusoff’s A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None provide tools to help us form a conversation around this piece.

Then there is Luanne Martineau’s After the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?, which deploys the figure of The Knitter Woman, a sculptural “kinetic mother figure” that spins yarn, producing a thin cord that eventually drops through the sculpture’s body and out through its legs, offering “the potential for creature comfort in the shape and form of an expanding circular rug to be sat and walked upon.” Again, this is an example of “extensive collective and cooperative action,” as this construction requires interaction by volunteers and gallery staff to produce the rug. I think again of Cvetkovich, who writes about the use of craft and craft materials in the art world, noting that it’s “central to the reclamation of feminist cultural politics as well as to crafting’s redefinition of what counts as politics to include sensory interactions with highly tactile spaces and with other people—or, in other worlds, feelings.”4 The way that this piece asks us to participate, to form, and to settle on something sensory—a rug constructed together with cord spun together out of yarn—and to generate feelings together is, in a very literal way, a form of nest building.

The next piece, Survivor by Cindy Baker and Ruth Cuthand, takes a more frank approach to the assignment, casting as their nest a hot tub positioned in front of a television upon which statistics, scientific findings, and news stories from the recent past scroll on loop. As they write in their own statement, “we sit in the hot tub and try to relax, and slow down, and talk about how to take care of each other, while we watch the world slowly die, while we slowly die.” This is an example of Donna J. Haraway’s idea of “staying with the trouble,” from her book of the same name, which carries the tenor of this particular piece: “Alone, in our separate kinds of expertise and experience, we know both too much and too little, and so we succumb to despair or to hope, and neither is a sensible attitude.”5 Survivor doesn’t ask us to find hope, but rather to find something more useful and more responsible with which to tend to the world. Alongside Staying with the Trouble, Dionne Brand’s long poem Inventory comes to mind as a text that might help us deal with the constant barrage of world-ending information via the news cycle.

Finally, we come to Jake Chakasim’s WAPIMISOW: Trickster Builds a Nest for the End of the World. In his artist statement, Chakasim writes that “as contemporary art and architecture continues to remind us of the atrocities experienced by Indigenous people, Chakabush, the Cree Trickster, further contemplates a way out of our unpleasant state by practicing one’s ‘Wapimisow,’” which he defines as a Cree word to “describe the ability to see a reflection of oneself physically, mentally and/or in a premeditated form.” Here, he combines the tipi, an architectural form with a rich and lengthy history, with materials from urban construction sites, creating a structure that is conversation with time and that makes material the relationship between the past and the present in ongoing settler colonialism. The very material of life has changed. I want to return to Kathryn Yusoff, who writes:

If the Anthropocene proclaims a sudden concern with the exposures of environmental harm to white liberal communities, it does so in the wake of histories in which these harms have been knowingly exported to black and brown communities under the rubric of civilization, progress, modernization, and capitalism. The Anthropocene might seem to offer a dystopic fixture that laments the end of the world, but imperialism and (ongoing) settler colonialisms have been ending worlds for as long as they have been in existence.”6

Again, the work of Billy-Ray Belcourt in NDN Coping Mechanisms resonates here, where he draws attention to the ways in which space and history collide in this place at the end of the world.

None of these pieces, artistic or literary, shy away from the fear, pain, and depression that imperialism, settler colonialism, capitalism, and the climate crisis bring into our lives. Indeed, the art in this exhibit ask us to stand before these feelings and to feel them, and then to think alongside those feelings. How did we get here? What home do we build here? Can we build something better? Ann Cvetkovich too asks us to fully face these feelings and urges us not to discard them as “bad” feelings that should be pathologized and put away. Instead, she writes, in the vein of Sara Ahmed, that “feeling bad might, in fact, be the ground for transformation.”7 Nests for the End of the World offers to us five opportunities to confront our bad feelings, places to think through the histories that we’ve inherited and that we contribute to recirculating, and offers us nests so that we might be held along the way.

Jason Purcell

Co-founder of the Glass Bookshop

*Please note: The interpretive space is now closed to the public, including access to the curated book selection/bibliography. We apologize for any inconvenience. Please reach out to Glass Bookshop with questions or orders.

1 Cvetkovich, Ann. Depression: A Public Feeling. Duke UP, 2012. 6.

2 Sharpe, Christina. In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke UP, 2016. 8

3 Qtd. In Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. U Minnesota P, 2018. 1.

4 Cvetkovich, Ann. Depression: A Public Feeling. Duke UP, 2012. 177.

5 Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble. Dupe UP, 2016. 4.

6 Yusoff, Katherine. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. U Minnesota P, 2018. Xiii.

7 Cvetkovich, Ann. Depression: A Public Feeling. Duke UP, 2012. 3.

These titles below have been carefully selected by our friends, Jason Purcell and Matthew Stepanic at Glass Bookshop.

Bibliography

- Belcourt, Billy-Ray, NDN Coping Mechanisms: Notes from the Field. Published by the House of Anansi Press Inc, 2019.

- Cheng Thom, Kai, I Hope We Choose Love, A Trans Girl’s Notes From the End of the World, published by Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019.

- Cvetkovich, Ann, Depression: A Public Feeling. Published by Duke University Press, 2012.

- Dimaline, Cherie, The Marrow Thieves. Published by DCB, 2017.

- Haraway, Donna J., Staying with the Trouble, Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Published by Duke University Press, 2016.

- Lappano, Jon-Erik and Hatanaka, Kellen, Tokyo Dig a Garden. Published by the House of Anansi Press, 2016

- Loveless, Natalie, How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation. Published by Duke University Press, 2019.

- Lowenhaupt Tsing, Anna, The Mushroom at the End of the World. On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Published by Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Major, Alice, Welcome to the Anthropocene. Published by The University of Alberta Press, 2018.

- Rice, Waubgeshig, Moon of the Crusted Snow. Published by ECW Press, 2018.

- Shotwell, Alexis, Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times. Published by the University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Thunberg, Greta, No One Is Too Small to Make a Difference. Published by Penguin Books, 2019.

- This Place: 150 Years Retold. Published by HighWater Press, 2019.

- Wallace-Wells, David, The Uninhabitable Earth. Life After Warming, Published by Tim Dugan Books, 2019.

- Yusoff, Kathryn, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Published by University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Nests for the End of the World is presented as part of the Poole Centre of Design.