The creation of an icon is an act of prayer, requiring the iconographer to have a deep knowledge of the traditions of theology, symbolism, and practice. Every aspect of the icon - from the choice of wood panel through to the finished image - is governed by these traditions. Not only should the iconographer understand the rules of image placement, geometry, proportion and colour, they must have practical expertise with artistic materials and techniques. Just like painters and other artists, iconographers and their workshops compiled manuals, pattern and recipe books. Some have survived, allowing us a glimpse into the iconographer’s workshop during the weeks’ long process of creation of an icon.

The workshop consisted of the iconographer at the top, supported by as many assistants as could be afforded. Much like a professional chef’s kitchen, roles and duties were clearly defined, the pecking order strictly observed. Pity the most junior of shop assistants: worrying over the strong-smelling pots of glue and spending years grinding by hand very hard stones into pigments, before they were ever given the chance to touch the icon.

Materials were sourced near and far, influenced by local traditions and cost. Local woods were often used for the panels, including cypress (that delicious ‘church’ smell) in the Mediterranean or linden in Russia. Glues were made from the skins of local rabbits or, if you could afford it, made from bladders of the beluga sturgeon imported from the Black and Caspian Seas. Common chalk may be mixed into ground alabaster to extend and brighten it. The colour black could come from the soot in the lamp in the workshop mixed with oil or wax. The colour blue for the Blessed Virgin Mary’s robe should always be the best of the best, the most expensive of the pigments: aquamarine, made from the stone ‘lapis lazuli’ found in Afghanistan.

The ancient technique of egg tempera for painting was most often used (and still is!) but is tricky to master. While it provides stability, brilliance and depth to the colours, the egg yolk will dry out or rot very quickly. Pigments are expensive and require a great deal of time to prepare, so every drop of colour is precious. Artists came up with clever ways to preserve the egg yolk and pigment mixtures with materials close to hand, including adding vinegar. Other liquids were added as preservatives, depending on geography: recipes include recommendations for fig juice in Italy, beer in Germany, or the fermented rye drink called ‘kvas’ in Russia.

Applying the tempera and the gold can be the most difficult parts. The surface of the icon must be pristine, as clean and smooth as possible to receive the colours and gold leaf. Layers of gesso (known as ‘levkas’ in Greek) made from alabaster or chalk mixed with rabbit skin glue was applied in layers, each layer burnished to sleek perfection. In order to achieve and maintain a flawless surface, dust in the workshop must be kept to a minimum. For any of us who have repainted a wall at home that was not properly prepared, we know that every bit of dust will appear as a glaring irregularity after the paint has dried. One of the ways to keep the dust down is to wet the floor of the workshop, just like vintage car restorers do when then are preparing the chassis for paint.

Even though many of the works we have on display were made hundreds of years ago, it is fascinating to discover that the techniques and materials used to make them are still in use today by contemporary iconographers and artists.

- Heather Pigat

Collections Manager, Art Museum at the University of Toronto

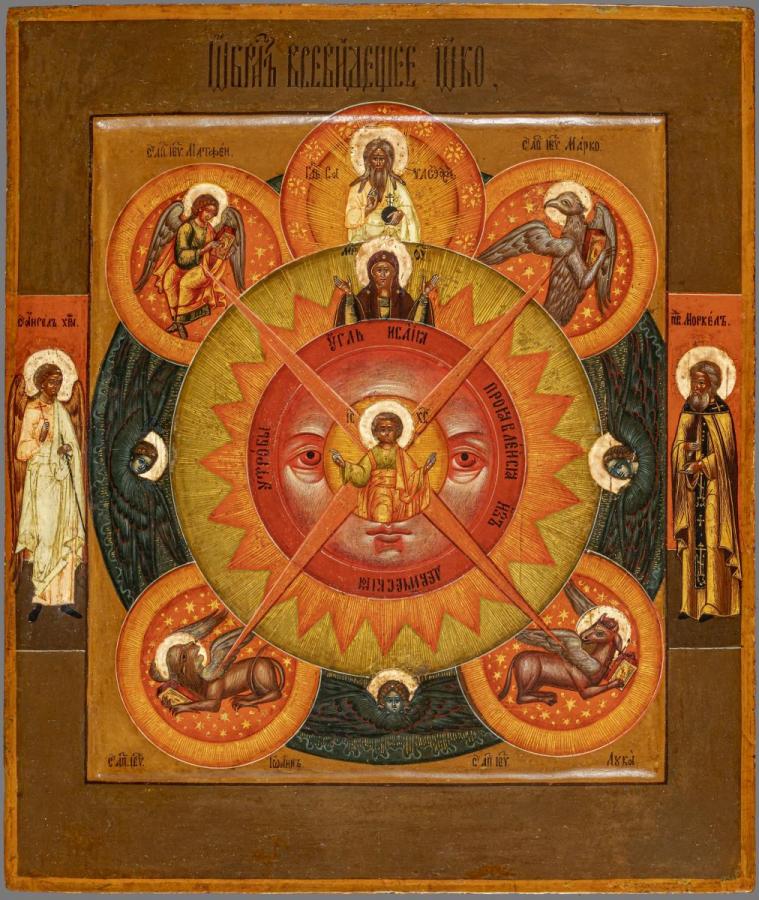

Image 1: All-Seeing Eye of God, tempera and gold on wood, Russian, 18th century. Gift of Dr. John Foreman, 2002. Malcove Collection. Courtesy of the Art Museum University of Toronto.

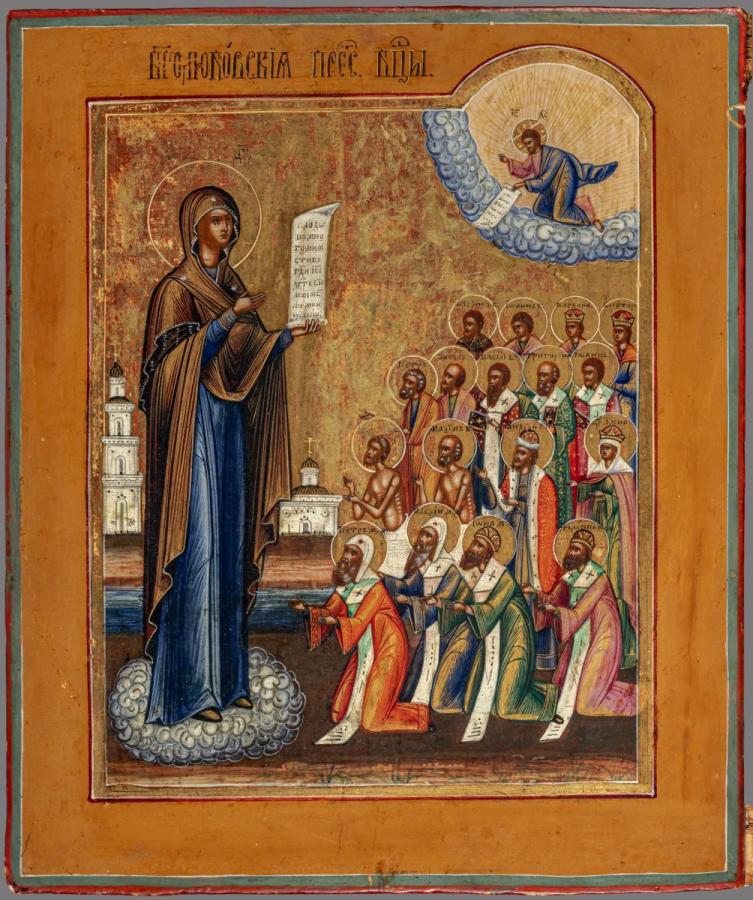

Image 2: Mother of God Bogoliubskyaya, tempera and gold on word, Russian, 17th century. Gift of Dr. John Foreman, 2002. Malcove Collection. Courtesy of the Art Museum University of Toronto.

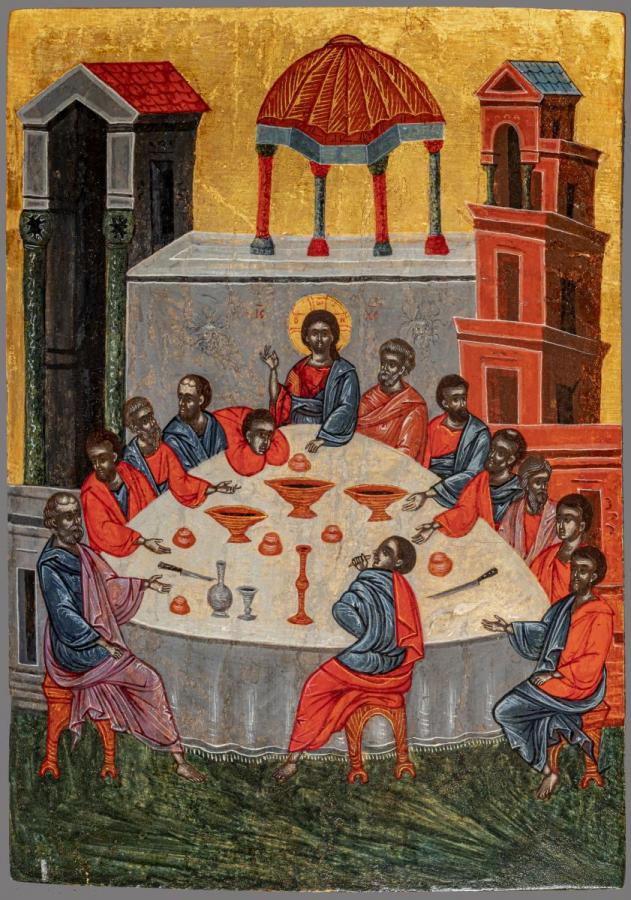

Image 3: The Last Supper, tempera and gold on wood, Serbian, 18th century. Gift of Dr. Lillian Malcove, 1982. Malcove Collection. Courtesy of the Art Museum University of Toronto.